It’s nearly impossible to discuss the cost, access, or quality of the U.S. health care system without circling back to Medicaid – the joint federal and state program that provides health coverage to those with low incomes. Since the creation of Medicaid in the 1960s, the program has traditionally covered the most vulnerable populations, including the poor, disabled, elderly, and those with children. Today, Medicaid covers one out of every five Americans and accounted for 36 percent of spending in the federal Department of Health and Human Service’s $1.1 trillion budget for 2018. The program started with limited scope and has evolved to cover more populations and more services. Most notably, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) created an opportunity for states to expand Medicaid programs to cover those with incomes that fall above the federal poverty level. The expansion would mostly be funded by the federal government.

North Carolina currently covers 18 percent of residents under Medicaid, which equates to roughly 2 million people. The state’s expenditures on Medicaid have grown slower than most other states during the previous decade. However, unlike most states, North Carolina has not expanded its Medicaid program. Regardless of whether states chose to expand Medicaid under the ACA, the combined state and federal expenditures for Medicaid have grown substantially from 1990 to the present. Medicaid programs are mostly funded by the federal government but left to states to administer. Thirty-nine states have had a federal waiver approved to change to a Medicaid “managed care” (MC) model for administering their programs. A few years after beginning the process of transitioning to a Medicaid MC state, North Carolina is close to completing the process sometime in 2019.

Traditional Medicaid includes a payment model that reimburses on a “fee-for-service” basis where each service is paid for separately. A transition to “managed care” would attempt to integrate all levels of care within one entity, called a managed care organization (MCO). An MCO is a combination of different private providers that would receive a capitated (or fixed) rate on a per-member-per-month basis. A capitated payment structure shifts coordination of care from state agencies to private providers participating in the managed care contract. In theory, if an MCO can coordinate the care of an enrollee, then there should be some savings and better health outcomes. Another benefit is that when moving to a fixed rate for each enrollee, the state expenditures are significantly more predictable year after year. The state sets guidelines for coverage that must be provided by the private insurers and providers who participate. The evidence is mixed, at best, whether MCO’s accomplish their goal of saving the state money and improving health outcomes by coordinating care and exporting the management of enrollees to private networks.

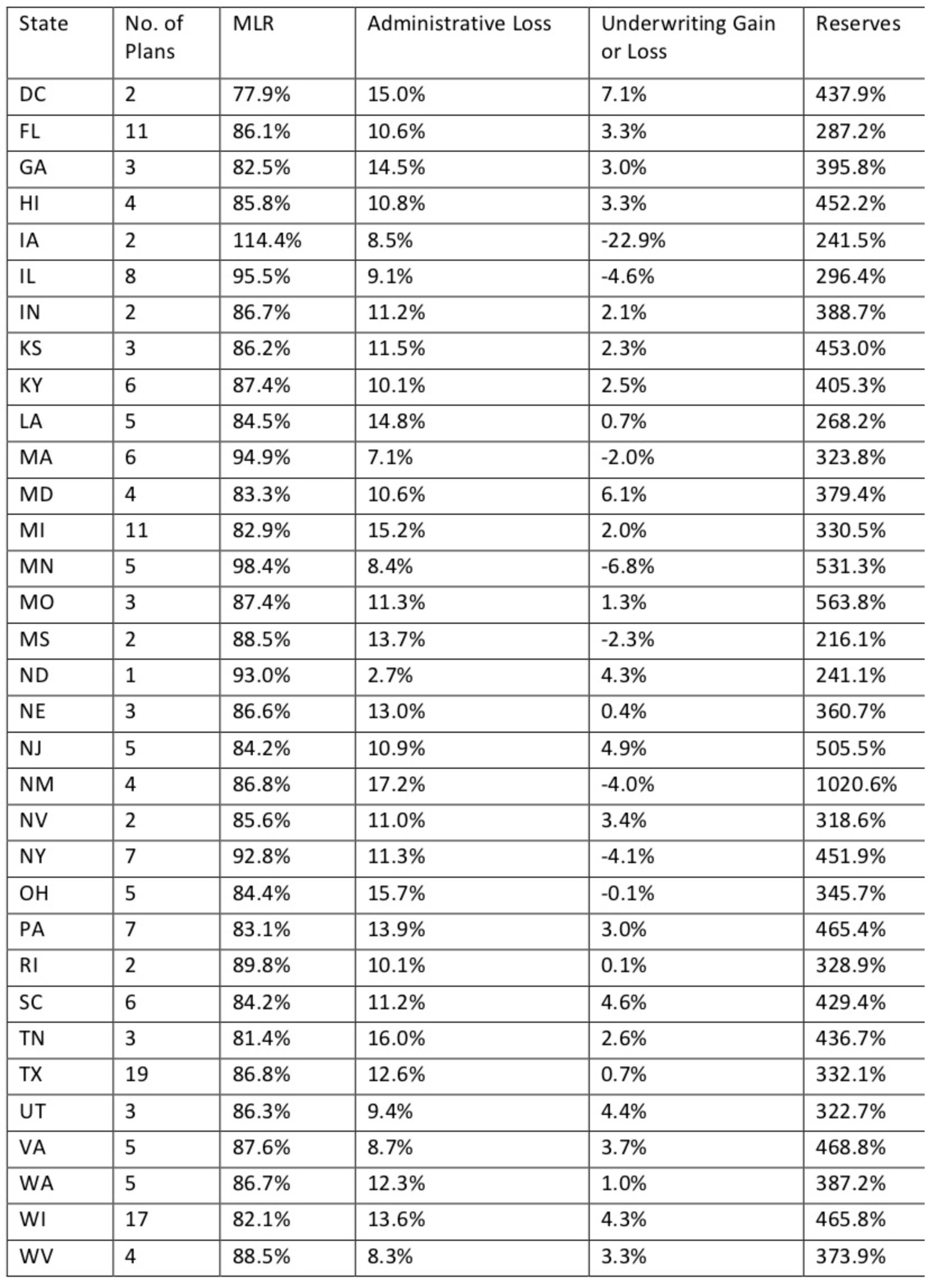

State transitions to “managed care” Medicaid programs must be approved by the federal government and as of this writing, the federal government has yet to approve the North Carolina plan. The state is hopeful that the waiver will be approved soon, thus allowing the state to begin its managed care program in mid-2019. Below is a chart compiled by Health Affairs that shows 2017 data for states that have switched to a Medicaid MC program:

Medicaid Managed Care Performance Measures

Source: Health Affairs

** California, Arizona, and Oregon have Medicaid Managed Care but are excluded because of incomplete data.

The data present an interesting picture of states who have already transitioned to a Medicaid MC program. One of the appeals of instituting a Medicaid MC program is the market-based incentives that would allow for different MCO’s to compete for the enrollees that are eligible. Thirteen of the current Medicaid MC states have three or fewer plans, thereby limiting the choices that enrollees have and competition between networks. Only four states have double-digit options. How many plans should be included in a state program? Medical loss ratio (MLR) is the proportion of money collected by the MCO that is paid out in benefits. This number varies by state. For example, Hawaii is only paying out 85.8 percent of program dollars collected, while New York is paying out close to 93 percent. MLR in the context of the health outcomes of an MCO provides us insight into how much value enrollees are getting for the money provided by taxpayers. What should the ideal MLR be?

Another appeal of MCOs is that by integrating and coordinating many of the services that the enrollees are receiving through the program, the amount of overhead and administrative costs would, in theory, decrease. The administrative loss column varies significantly for the amount of money that each state spends to administer the program. For example, Ohio has significantly more people enrolled in their managed Medicaid program (2,400,000) than New Mexico (600,000), yet the administrative costs are 15.7 percent and 17.2 percent, respectively. Medicaid MC programs are designed to relieve administrative costs. This proportion of spending on administrative costs compared to the number of enrollees tells us how efficient the managed care system may be working. How much is too much spending in this category? Further, the reserves of the state’s programs vary significantly. Do states with higher reserves need to spend more? Do states with lower reserves need to save more? These are a few of the many questions states must consider when deciding how their program will operate.

The data in the above chart do not capture the whole picture of a state’s Medicaid MC. However, it does show one thing for certain – the productivity of the programs varies greatly by state. The amount that the plans spend on benefits, the cost of running the program, and the amount of money kept in reserves for emergencies all differ. The lesson this offers is that it is not always the amount of money spent on administrative costs, actual benefits, or kept in reserves that matters most. A successful program may have more to do with the state understanding the population and coordinating resources to spend each program dollar as wisely as possible. By switching to a Medicaid MC structure, North Carolina is accepting the challenge of coordinating care of enrollees within private plans to spend taxpayer dollars as efficiently as possible, while also providing better care for the beneficiaries.

Medicaid is a unique program. It serves vulnerable, high-risk populations that need assistance, and funding for the program comes from a partnership between the federal and state governments. Given its unique nature, it’s no surprise that implementing a managed care program will be challenging. The disparity of successes and failures of other states’ managed care programs poses a serious challenge to North Carolina policymakers and agency officials to ensure that they get this right. According to the official proposal, this program seeks to “implement Medicaid managed care in a way that advances high-value care, improves population health, engages and supports providers, and establishes a sustainable program with predictable costs.” The plan will offer four statewide plans and as many as 12 smaller provider-led entities for North Carolinians to choose from.

There is enough evidence to show that a well-designed Medicaid managed care program can be beneficial to the enrollees it serves and the taxpayers that fund it. A Medicaid managed care program should be viewed as a long-term contract between the state, providers, and enrollees. Are North Carolina and the providers who contract with the state up to the challenge? Careful analysis in the years to come will provide the answer.