A lighter post for your Friday…

Twitter usually is good for negativity, and people lobbing insults at each other. However, the other night while I was scrolling through the website, I came across a particularly interesting article. The article discusses a concept that I have never heard of: floating hospitals.

What? A floating hospital? Why? To treat patients while containing the spread of disease.

Author Bill Gourgey wrote an article recently calling for the reconsideration of floating hospitals in the time of coronavirus. As we think about how to contain future viruses, this may be a worthwhile consideration. Gourgey writes,

In an attempt to address the tuberculosis (TB) pandemic in the early 20th century, which killed an estimated 450 Americans each day, a U.S. engineer proposed a more creative solution: quarantining the sick in floating hospitals dubbed “Aerial Sanatoria.” Though the idea was technologically far-fetched at the time, it is worth reconsidering today.

Known as the White Plague for its victims’ sickly white pallor, TB, a respiratory disease, was a leading cause of death in the United States from the country’s founding to well into the 20th century. During the height of the pandemic, and especially after scientists determined in 1882 that TB was caused by a contagious pathogen and had no cure, the sick were encouraged to attend and often forced into sanatoria, medical facilities built to isolate people with long-term illness. The sanatorium movement was driven by public health officials who wanted to contain the contagion and by progressive public health reformers who sought a controlled medical research setting in which experimental cures could be administered and patient recovery monitored. According to Mayo Clinic Proceedings, the first American sanatorium, built in the Adirondacks in 1885, promoted isolation in a “salutary environment” and became a model for others to follow. By 1925, the United States had 536 sanatoria with nearly 700,000 beds — from which, according to a 2006 report published in the journal Respiratory Medicine, the majority never returned.

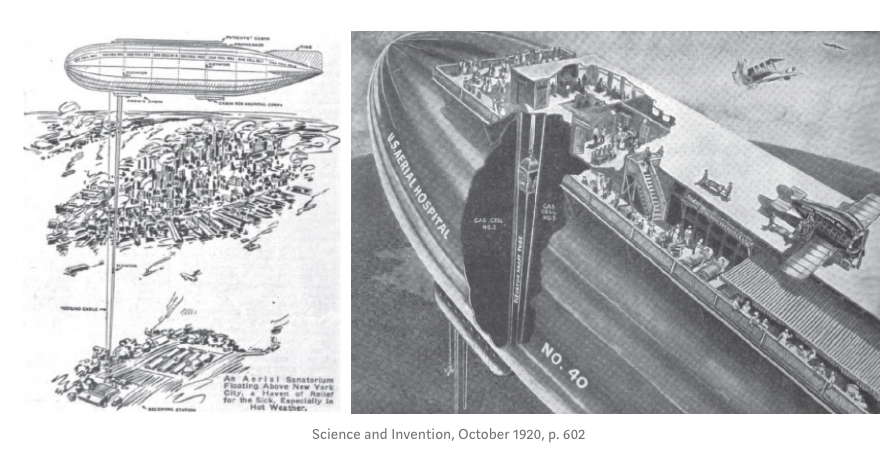

In the October 1920 edition of Science and Invention, Flavius Earl Loudy, a University of Michigan graduate who holds the distinction of earning the world’s very first bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering, described a solution that was both humane and, just as importantly, mobile. “Instead of transporting tuberculosis patients to the sanatorium, we should bring the sanatorium to the patients,” Loudy wrote in his piece, titled “An Aerial Sanitorium.” He delivered elaborate schematics and detailed descriptions of “great Zeppelins” that could be outfitted as aerial hospitals: “The patients’ cabin is located on the top of the airship so as to get as much sunshine as possible, while the airship crew… and hospitals corps” occupy lower cabins. In Loudy’s vision, “Food supplies, as well as people, are conveyed to and from the airship by means of an electric hoist in the forward car or cabin. Patients who cannot stand the trip up to the airship can be carried up by an airplane ambulance… the airplane landing on or hopping off from the giant upper deck easily.”

Is it so crazy? Remember, just like this floating hospital idea, telemedicine was first considered in the early 20th century. The people who thought of these innovations were ahead of their time. Now it is a reality that many providers and patients currently use.

Throughout the current coronavirus pandemic, a major point of discussion has been the balance between the need to contain the virus and the economic impact that comes from mandating businesses close their doors. As Gourgey writes,

Loudy’s idea was meant to address both economic and medical imperatives. Most people could not afford the expense of traveling to rural sanatoria, yet doctors believed that the dry, high-altitude mountain air and sunshine improved chances of recovery. An aerial hospital solved both. While the cost and ease of transportation and the quality of medical care have advanced significantly since Loudy’s day, so has the frequency, velocity, and scale of our disasters. The need to rapidly deploy supplementary, state-of-the-art medical care — including the ability to properly quarantine — to regions of the world where existing medical infrastructure has been overwhelmed by contagion or crippled by catastrophe has never been greater.

Obviously, an idea like this won’t do much to help stop the spread of the current coronavirus. But once the dust settles, and the world returns to normal, floating hospitals could be considered as a possible solution before the next pandemic.

Read the full article here.