It’s that time again. Time for Wake residents to brace themselves as the county reappraises residential and commercial property values. Wake County property owners may be less fortunate in this area than their fellow North Carolinians because, according to a research brief recently published by JLF’s Joe Coletti:

Wake County has increased the revaluation-adjusted property tax rate by 40 percent since 2014, with six increases in the past six years. Wake County now has higher tax rates than Mecklenburg County.

To promote transparency in property tax changes, Coletti explains:

North Carolina has long required local governments to advertise the tax rate required to generate the same revenue based on the new property values. However, local governments can raise the tax rate as normal during the budget process.

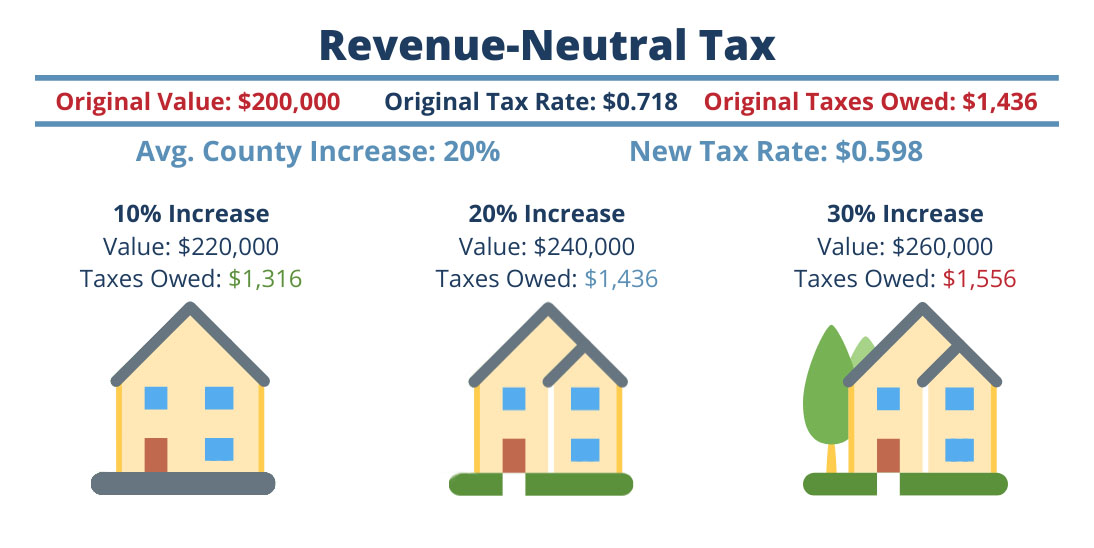

This rate is called the revenue-neutral rate. Under a revenue-neutral rate, the county is not supposed to take in any more revenue than it did the previous year. So, if your home value goes up at the same rate as the county average, the amount you pay in taxes stays the same; if the increase in your house’s value was less than the average, you pay less, and if it was more, you pay more. Below is an example of what a revenue-neutral tax would look like for Wake County since the average increase in property values was 20 percent.

Coletti explains:

For a typical homeowner, the practical implication is this: If you had a $200,000 house and the tax rate was $0.718 (or 7.18 mills for new transplants), your tax would be $1,436. A 20 percent valuation increase, equal to the county average, would put your home value at $240,000. With a revenue-neutral tax rate of $0.598, you would still pay $1,436 in taxes. If your home value jumped 30 percent to $260,000, you would pay $1,556. But if your house increased 10 percent to $220,000, your tax bill would fall to $1,316.

A taxation model based on property values potentially disincentivizes homeowners to make improvements to their property. Coletti explains:

An old idea that has been gaining favor again would be to replace the property tax, which penalizes welfare-enhancing improvements to land, with a land value tax. Charles Marohn, president of Strong Towns, argues a land value tax “rewards neighborhood investments, discourages idleness, and closely aligns private gain with the public good.” Experiments with a type of land value tax in Pennsylvania have increased development since the 1980s, but Altoona abandoned a full land value tax in 2017.

Read the full piece here, and learn more about N.C. housing here.