Dr. Gajendra Singh, a Winston-Salem surgeon, is suing the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) over its Certificate of Need (CON) law related to MRI machines.

CON laws require hospitals and other health care facilities to apply for permission slips from the state to expand their services. Under this system, the state – not the doctor or hospital – determines what is ‘needed’ and what is not. This artificially restricts the supply of hospital beds, scanners such as MRIs, and life-saving medical devices.

The case has had many twists and turns. This week, JLF’s Jon Guze wrote about just one of the many hurdles this case will face. Guze writes:

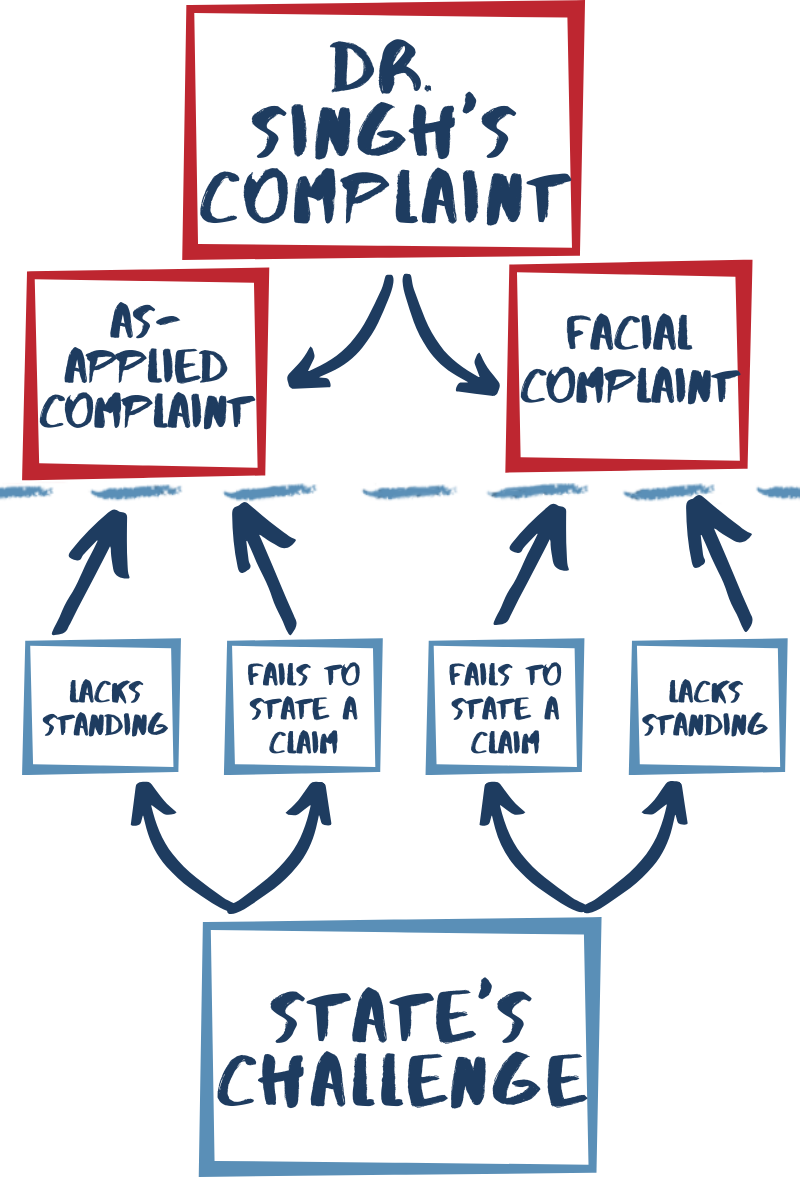

Dr. Singh filed a complaint in Superior Court, alleging that the certificate of need (CON) law violates the state constitution both as it applies to his particular circumstances and on its face.

His complaint to the law as it applies to his particular circumstances is his “as-applied” challenge. His complaint to the law as a whole is his “facial” complaint. This means, if Dr. Singh’s as-applied complaint succeeds, only he can receive remedy. If his facial complaint succeeds, however, the law will be overturned altogether.

The state replied to Dr. Singh’s lawsuit with a motion to dismiss the case. Guze explains:

The State of North Carolina filed a motion to dismiss the complaint because, under Rule 12(b)(1) of the North Carolina Rules of Civil Procedure, Dr. Sing lacked standing to bring the lawsuit, and because, under Rule 12(b)(6), Dr. Singh had failed to state a claim for which relief may be granted. (Emphasis added)

In other words, the state wanted to dismiss the case for two reasons: (1) Dr. Singh lacked the standing to bring a lawsuit, and (2) Dr. Singh did not state a claim for relief (see diagram below).

A new rule (42(b)(4) if you are interested) has, however, shaken things up a little bit. The rule requires Dr. Singh’s as-applied complaint to be ruled on by a Superior Court judge, Gregory McGuire, but his facial complaint to be decided by a three-judge panel of superior court judges. Splitting up a lawsuit this way is called “bifurcation,” and it makes the lawsuit significantly more expensive and time-consuming. Guze explains:

By requiring a separate process of judicial review for facial challenges, the rule has the direct effect of making constitutional challenges more time consuming and more expensive simply because it means there have to be more filings, more hearings, and more legal work of every kind.

This, in effect, makes it more difficult to challenge the constitutionality of a law in North Carolina.

What is worse, the law is unclear as to when a judge can decline to rule on motions to dismiss as-applied complaints on the basis that they fail to state a claim for relief. This confusion about whether or not Judge McGuire could abdicate making a decision on this matter led him at first to decline to make a decision; however, eventually, McGuire did make a decision, but it was not in Dr. Singh’s favor. At least now, the case can go on with Singh’s appeal on the ruling. Guze writes:

The fact that Judge McGuire reconsidered his previous decision and handed down a ruling about the as-applied aspect of the State’s 12(b)(6) claim is good news in itself because it means the case won’t be placed on hold for months or years while a three-judge panel is convened to rule on the 12(b)(6) claim …. It would have been even better news if, having decided to rule on that part of the State’s motion, Judge McGuire, had denied the motion, but, unfortunately, that’s not what he did.

One thing is for sure. This is bound to be just the first in a series of hurdles this case will face.

Read the full article and see what caused the confusion over Judge McGuire’s opinion here. You can also read Guze’s amicus brief on the court case here.