“There is no such thing as abstract truth.” Vladimir Lenin warned the world, years ago. Socialists at their most extreme will put everything, even the idea of objective truth, under their boots.

“An organizer working in and for an open society is in an ideological dilemma. To begin with, he does not have a fixed truth—truth to him is relative and changing; everything to him is relative and changing. He is a political relativist.” Saul Alinsky, the ideological inspiration for Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton and countless other socialists and “progressives,” wrote this in “Rules for Radicals” in 1971.

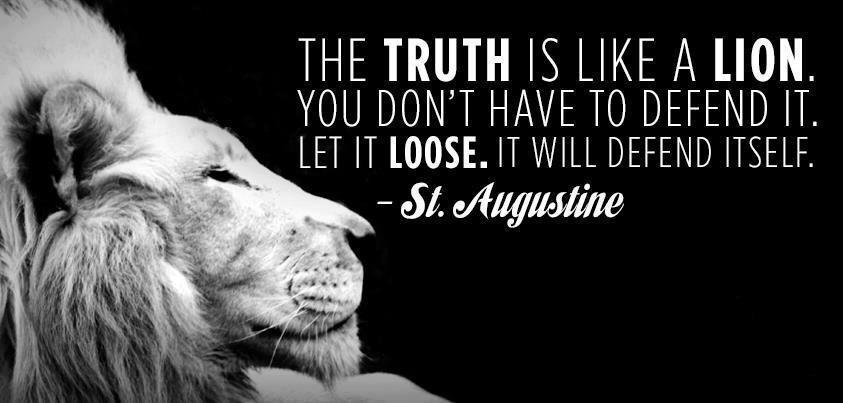

Thing is, however, most people still hold to the belief that objective truth exists, and it is above politics and other human endeavors. It is for that very reason I predicted back in 2016 that media and progressives would rue trying to blame “fake news” for Donald Trump’s election.

Thing is, however, most people still hold to the belief that objective truth exists, and it is above politics and other human endeavors. It is for that very reason I predicted back in 2016 that media and progressives would rue trying to blame “fake news” for Donald Trump’s election.

Why? Because they were unwittingly upholding an objective standard when they prefer to traffic (see above) in relativism — i.e., the “narrative” by which they tell the general public the story they wish them to believe in order to accomplish their political goals of the moment.

But the general public thinks of news as the who, what, when, why, where, and how. They see fake news as lying.

The progressive drive for a clever redefinition of lying

Going back to my days covering higher education, I’ve followed the various ways progressives have tried to put the appropriate word dressing on a lie to make it seem like the truth. A few notorious efforts include:

- “Correct in mythical terms”

- “Fake but accurate”

- “Tells essential truths”

- “Certain lies are good”

- “Truthiness”

The narrative this week sorely needs the general public to believe the salacious details in the Michael Wolff book about President Trump. This is a Herculean task (the Augean stables come to mind) given that it’s crammed with obvious errors, and exponentially more so because Wolff’s own prologue doubts whether things he wrote are true.

Wolff explained the link between his book and truth this way: “If it makes sense to you, if it strikes a chord, if it rings true, it is true.”

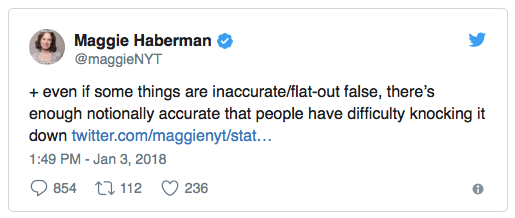

The New York Times’ Maggie Haberman came up a different term for that approach:

“Notionally accurate”: a lie is true if it sounds true to someone inclined to believe it.