The FTC has a new Economic Liberty Task Force to focus on state occupational licensing activities. Acting FTC chairman Maureen Ohlhausen announced it in a March 31 speech at George Mason Law Review’s antitrust symposium.

Primarily, the FTC’s interest in Economic Liberty will be advocacy and partnership. But Ohlhausen is not averse to fighting for economic liberty in court. It’s worth noting — as a January 2017 Reason magazine profile of her did — that “North Carolina Dental is Ohlhausen’s greatest achievement so far as an FTC commissioner.”

Meaning the 2015 Supreme Court decision in North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission, which dismantled the presumption that state occupational licensing boards are automatically immune from federal antitrust laws. In the Court’s opinion, a state licensing board may violate federal antitrust law if a controlling number of board members comprise “active market participants” regulated by the board but the board is not actively supervised by the state.

As Ohlhausen told the antitrust symposium,

Occupational licensing stands out as a particularly egregious example of this erosion in economic liberty. In the 1950s, less than five percent of jobs required a license. Estimates today place that figure between 25 and 30 percent. Today, licensing requirements reach far beyond doctors, electricians, and other fields where public health and safety issues are clearer. Instead, licensing requirements extend to auctioneers, interior designers, make-up artists, hair-braiders and numerous other occupations.

The public safety and health rationale for regulating many of those occupations ranges from dubious to ridiculous. Consumers can, and do, easily evaluate the quality of interior designers, make-up artists, hair-braiders, and others. I challenge anyone to explain why the state has a legitimate interest in protecting the public from rogue interior designers carpet-bombing living rooms with ugly throw pillows. Market dynamics will naturally weed out those who provide a poor service, without danger to the public. For many other occupations, the costs of added regulation limit the number of providers and drive up prices. These costs often dwarf any public health or safety need and may actually harm consumers by limiting their access to beneficial services.

What is the FTC’s role in this? Ohlhausen said:

Of course, in some instances enforcement may be an appropriate tool, consistent with the Supreme Court’s ruling in North Carolina Dental and other state action cases. This is particularly the case when the “Brother, May I?” problem exists. Active market participants still control many state boards that impose licensing restrictions. Thus, the question revolves around whether the state is actively supervising the board actions that displace competition. When warranted, the FTC will bring enforcement actions in appropriate cases.

In consequence, The National Law Review expects there will be “an increase in FTC actions involving licensing boards.” It counsels:

Licensing boards and those who are involved in licensing regulations should examine the ways in which the regulation affects or could affect competition, whether there is evidence that a regulation is necessary to achieve the targeted policy goal, whether the regulation is narrowly tailored to meet the policy goal, and whether a less restrictive alternative is available to achieve the policy goal and benefit competition.

If North Carolina leaders needed more reasons to reform occupational licensing and bring more labor freedom here, this approach from the FTC should suffice.

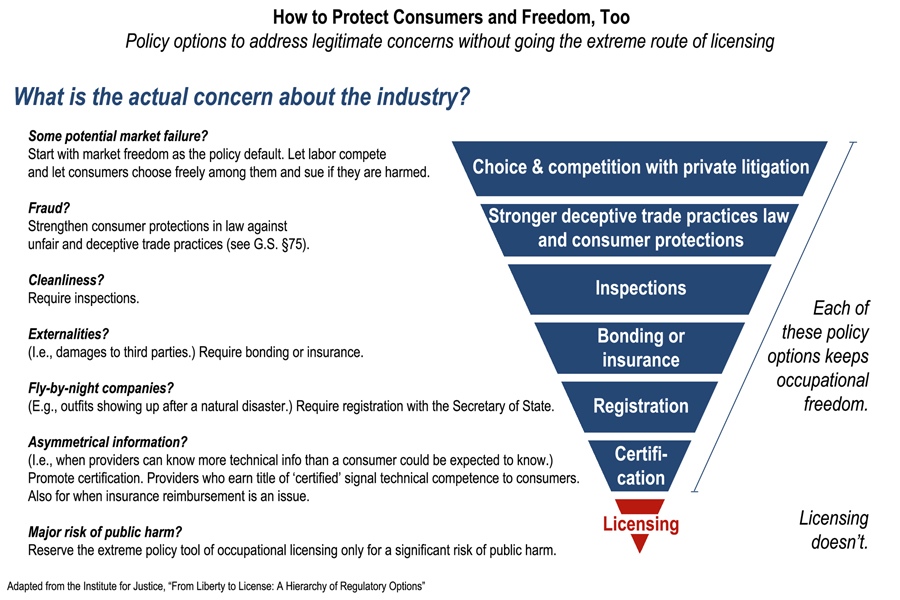

The Institute for Justice uses an inverted pyramid to depict the many policy options available. I expand upon that below (click the image for the full size):