The legal temerity is truly shocking. The Indiana Supreme Court recently handed down a decision declaring the ancient common-law right to resist unlawful entry of one’s home by police officers invalid in Indiana. Yes, Hoosiers, your judiciary has decided the 4th Amendment protection of a citizen’s home from unlawful search and seizure (reiterated word-for-word in the 11th Amendment to the Indiana Constitution) does not extend to any resistance of an unlawful assault or invasion, reasonable or otherwise–the court claims civil remedies at law after-the-fact are sufficient protection, concluding “public policy disfavors any such right” to resist.

In Barnes vs. State, the court by a 3-2 majority noted the ancient common-law origins (possibly back as far as the Magna Carta) of the right to reasonably resist unlawful arrest or entry of one’s home, even citing the U.S. Supreme Court’s repeated upholding of the right, but decided by fiat to step far beyond even more recent precedent that is slowly chipping away at Fourth Amendment rights. The case was complex–an officer forced his way into an apartment after a call about a non-violent domestic disturbance, and upon some resistance by the homeowner, “used a choke hold and a taser to subdue him.” Upon recovery (the homeowner suffered an “adverse reaction to the taser” and was taken to the hospital) he found himself charged with disorderly conduct, resisting a police officer, battery on a police officer, and interference with reporting of a crime. The trial court refused to instruct the jury on the legality of resisting an unlawful entry, and the Court of Appeals ordered a new trial on appeal. The Supreme Court, faced with the case, did not uphold the age-old right of sanctuary from unlawful entry, nor did they opt to extend the “exigent circumstances” that legalize warrantless entry in critical situations to cover the entry in a case of domestic disturbance.

Rather, in a shockingly irresponsible piece of jurisprudence, the majority chose to deny this basic right to all Indiana citizens on the rather shaky grounds that affirming the right would merely encourage violence that would be unlikely to change the result. In their reasoning, the justices also concluded that modern legal process has made the need for such a right obsolete, with modern police procedure, disciplinary action, and civil actions at law providing sufficient protection for the citizen. “We believe … a right to resist an unlawful police entry into a home is against public policy and is incompatible with modern Fourth Amendment jurisprudence,” writes Justice Steven David in the majority opinion.

The opinion has deservedly raised hackles, with widespread legal and political outcry in Indiana and nationwide. The two justices in the minority of the decision released dissenting opinions, one urging a more cautious revision of the common-law right to only cover “reasonable” resistance, and another decrying the overriding of Constitutional right and Supreme Court precedent, when “[t]here is simply no reason to abrogate the common law right of a citizen to resist the unlawful police entry into his or her home.” Seventy-one Indiana lawmakers have joined together to file an amicus curiae brief requesting the court rehear its decision in the light of its dangerous precedent–criminals have been known to impersonate police officers before, should citizens just surrender to any unlawful entry by apparent police officers? Doug Powers, writing at MichelleMalkin.com, goes one step further and asks what recourse might the citizen have whose home is invaded if evidence might be planted that excuses the invasion after the fact?

As suspect as this decision is, it is simply the latest step in a national shift toward even more irresponsible and unconstitutional jurisprudence–which has climaxed in Indiana with multiple decisions eroding the citizen’s common-law and constitutional protection from unreasonable search and seizure, including a pair of cases issued two days before Barnes affirming that an officer does not need to seek prior judicial approval of a “no-knock” warrant to enter and serve a warrant without announcing his presence. Combined with Barnes, these cases significantly erode the rights of an Indiana citizen under the Fourth Amendment, allowing a police officer to enter and serve a warrant without announcing his presence, and enjoining the citizen not to resist his entry, whether he possesses a lawful warrant or not.

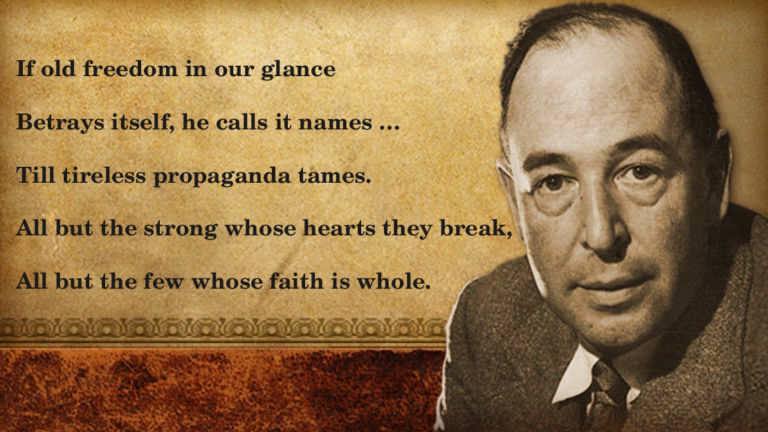

Retired lawyer and staunch conservative author John C. Wright says it best in his damning analysis of the case here:

The chutzpah needed to overturn a basic principle of the law and of the rights of man dating back to AD 1215 is simply astonishing, almost awe-inspiring. The legal eccentricity of Emperor Caligula forcing the Senate to vote him to be a god is the only thing of comparable magnitude I can imagine. Overturning the Fourth Amendment by judicial fiat is minor in comparison.