George Washington earns a spot in the American history books as both the commander of the army that won the Revolutionary War and the first president of the United States. It makes sense that most biographies of Washington would focus heavily on those two periods of his life — each of which extended over roughly eight years.

What about the more than five years of activity between those two important chapters in Washington’s life? Biographers often treat this “interlude” as a time when the retired general focused on his life as a Virginia planter at home in Mount Vernon, and eventually his work as chairman of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

What about the more than five years of activity between those two important chapters in Washington’s life? Biographers often treat this “interlude” as a time when the retired general focused on his life as a Virginia planter at home in Mount Vernon, and eventually his work as chairman of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

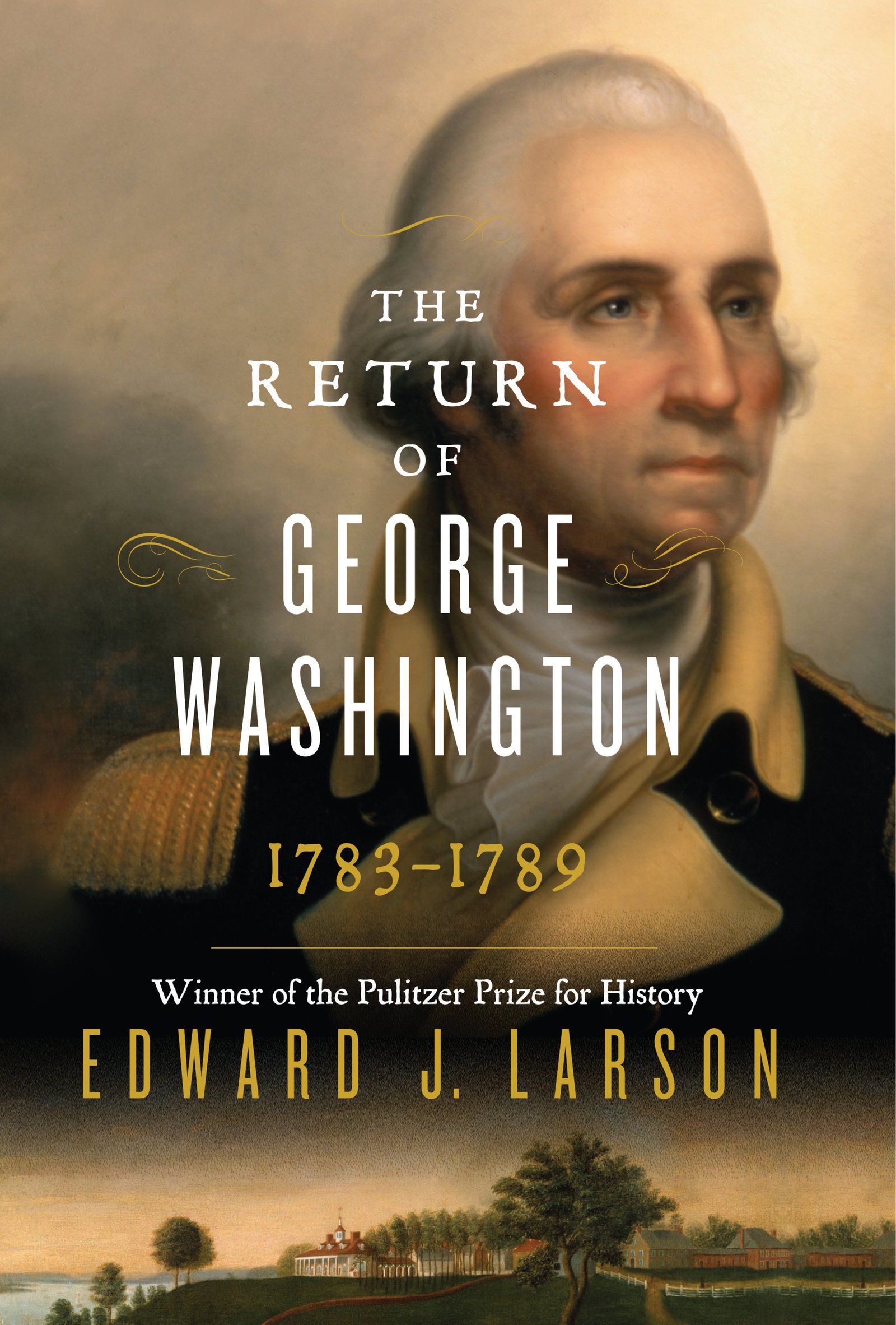

But Pulitzer Prize-winning history professor Edward Larson of Pepperdine University thinks the time period between Washington’s departure from the U.S. Army in late 1783 and his inauguration as president in early 1789 deserves much more scrutiny. That’s the idea behind The Return of George Washington 1783-1789.

While Washington held no national public office at that time, Larson argues that it would be a mistake to believe that the retired general played no significant role in the nation’s political debates. Larson explains how Washington influenced national political developments throughout the period extending from the revolution’s end until the launch of a new constitutional government.

Over the course of 1788, Washington had articulated three main objectives for America under the Constitution: respect abroad, prosperity at home, and development westward. Toward these ends, he envisioned a vigorous federal government encouraging trade, manufacturing, and agriculture through effective tariffs, sound money, secure property rights, and a nonaligned foreign policy. “America under an efficient government, will be the most favorable Country of any in the world for persons of industry and frugality,” he asserted in mid-1788, and “not be less advantageous to the happiness of the lowest class of people because of … the great plenty of unoccupied land.”

Larson contends that the period between the war and the presidency played a pivotal role in making true Henry Lee’s well-known assertion that Washington was “First in war — first in peace — and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

The third, the one that Washington would have most treasured, relates in large part to the trust and affection he earned between those two periods of official service, when he voluntarily relinquished power yet never stopped nurturing the new republic. Washington was as indispensable to America during these middle years as before or after them. During that pivotal phase of the country’s development, he laid the foundation for the Constitution, the government, and the sacred union of states and people that has lasted for more than 225 years and promises to continue long into the future.