Film industry supporters who want the state to continue giving their industry generous tax credits like to tout NC State professor of supply chain management Rob Handfield’s study of those credits. They also like to make it seem as if the study is from NC State.

Take the recent pro-incentives column by Wilmington author Wiley Cash in the N&O. Along with citing famous NC productions that were filmed well before the state offered film incentives (which seems to be standard practice), Cash stated:

A recent study of North Carolina film incentives conducted by N.C. State University’s Poole College of Management found that from 2007 to 2012 every $1 in tax credits led to $9 in spending, which resulted in $1.50 of tax revenue that went directly into state coffers.

About his findings, see below. About who conducted the study, I would think such a fact ought to have been checked by an editor, but maybe editing rigor is dependent upon the perceived rightness of the cronyism. Or maybe the editors had assumed Handfield was acting in official university capacity, given that, as reported by Carolina Journal in April 2014 (pdf link, see p. 14):

Handfield released some of his findings Nov. 8 in a two-page letter on university stationery to Wilmington Film Commission Director Johnny Griffin.

CJ noted, however, that

Handfield’s study is not sanctioned by N.C. State, even though some have referred to it as the “N.C. State Study.”

So who did sanction it? Paul Chesser investigated, and here is what he found:

According to a Feb. 24 email from Beth Petty, director of the Charlotte Regional Film Commission, North Carolina State University’s Robert Handfield – a professor of supply chain management in NCSU’s Poole College of Management – was paid $45,000 to produce research to “assist our efforts in demonstrating how important the film/TV industry is to our state and economy.” In an interview with The News & Observer of Raleigh earlier this year, Handfield refused to disclose how much he received for the study but said he was “grossly underpaid for the amount of work that went into it.”

Petty revealed in the message the majority of funding for Handfield’s study – $25,000 – would come from the Motion Picture Association of America, a group that boasts several powerful Hollywood studios as members, including Disney, Paramount, Sony Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Universal and Warner Brothers. Among its many advocacy functions, MPAA promotes tax breaks and incentives for the industry at the state level. …

In addition to MPAA’s $25,000 commitment, [Petty] revealed that the Wilmington Regional Film Commission pledged $10,000 and the Charlotte commission promised $7,500. That left a shortfall of $2,500 for the $45,000 that Handfield required, of which the Western North Carolina commission paid half ($1,250), which an organization official emphasized came from private funds supplied to the agency, not public money.

The report bought at $45 grand by the MPAA and regional film commissions was riddled with errors. Presumably, if the industry wanted a study that properly accounted for opportunity costs and avoided, in the words of Fiscal Research’s analysis of it, “a series of misunderstandings of the State’s tax laws, invalid or overstated assumptions, and errors in accounting valid assumptions,” the industry would have gotten it. So it seems reasonable to assume that what the industry paid for was what they cite: the study’s ready-for-distribution, incredibly over-the-top figures on return on investment and jobs involved, and maybe also the ease of saying the study was done by NC State.

A note about the findings: It should be hard to believe that politicians from various other walks of life (and not, say, professional investors and entrepreneurs interested in profit maximizing) would have stumbled across a Deal of a Lifetime Investment Opportunity when so many other states were getting next to nothing doing the same thing, but that’s exactly what industry boosters wished state leaders to believe.

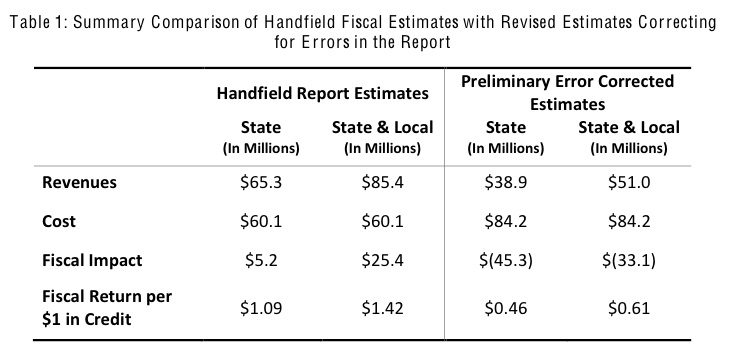

Fiscal Research adjusted for “the most serious errors” in the report and found no deal of a lifetime, just yet another negative return on investment from a state incentive program (the following table is from the Fiscal Research analysis):

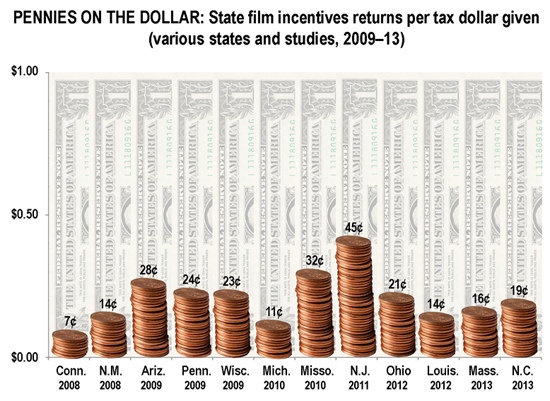

Nevertheless, Fiscal Research evaluated the Handfield report on its own methodology, so it admittedly also didn’t account for opportunity costs. A previous estimate by the Commerce Department made some accounting for opportunity costs and found the return on investment to be not 46 cents per dollar, but just over 19 cents per dollar.

That finding was well in line what other states were returning from their own film incentives: