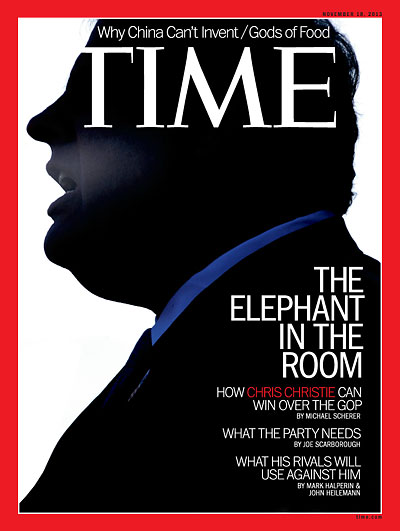

Those intrigued by the prospect of Chris Christie running for president in 2016 might enjoy Joe Scarborough’s column on the topic in the latest TIME.

Those intrigued by the prospect of Chris Christie running for president in 2016 might enjoy Joe Scarborough’s column on the topic in the latest TIME.

Next year marks the 50th anniversary of the nomination of Barry Goldwater and the shouting down of Nelson Rockefeller at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. For many conservatives, the Goldwater moment–itself a reaction to the perceived moderation of the Eisenhower years–is a kind of nativity narrative for what’s best about the modern GOP. The story goes like this: conservatives disenchanted with Ike nominated Goldwater, whose defeat made Reagan’s ultimate victory possible.

The problem with that tale, though, is that it fails to credit the great historical fact of the matter: Eisenhower and Reagan had more in common with Christie than with Ted Cruz. Ike and Reagan knew how to win and how to govern, and they bent history to their will by appealing not just to a narrow slice of America but to the nation–even the world–as a whole. …

… To win again–to make America great and growing again–requires a return to the spirit and substance of Eisenhower and Reagan. We Republicans will not win national elections if we do not broaden our appeal in the way these giants did. Nor will we govern well if we refuse to make principled compromises when necessary, the kinds of compromises that led Ike and Reagan to historical greatness.

Meanwhile, a book excerpt in the same issue focusing on Mitt Romney’s decision to drop Christie as a potential running mate last year will raise red flags about the New Jersey governor’s ability to wage a successful campaign for the White House.

The list of questions Myers and her team had for Christie was extensive and troubling. More than once, Myers reported back that Trenton’s response was, in effect, Why do we need to give you that piece of information? Myers told her team, We have to assume if they’re not answering, it’s because the answer is bad.

The vetters were stunned by the garish controversies lurking in the shadows of his record. There was a 2010 Department of Justice inspector general’s investigation of Christie’s spending patterns in his job prior to the governorship, which criticized him for being “the U.S. attorney who most often exceeded the government [travel expense] rate without adequate justification” and for offering “insufficient, inaccurate, or no justification” for stays at swank hotels like the Four Seasons. There was the fact that Christie worked as a lobbyist on behalf of the Securities Industry Association at a time when Bernie Madoff was a senior SIA official—and sought an exemption from New Jersey’s Consumer Fraud Act. There was Christie’s decision to steer hefty government contracts to donors and political allies like former Attorney General John Ashcroft, which sparked a congressional hearing. There was a defamation lawsuit brought against Christie arising out of his successful 1994 run to oust an incumbent in a local Garden State race. Then there was Todd Christie, the Governor’s brother, who in 2008 agreed to a settlement of civil charges by the Securities and Exchange Commission in which he acknowledged making “hundreds of trades in which customers had been systematically overcharged.” (Todd also oversaw a family foundation whose activities and purpose raised eyebrows among the vetters.) And all that was on top of a litany of glaring matters that sparked concern on Myers’ team: Christie’s other lobbying clients, his investments overseas, the YouTube clips that helped make him a star but might call into doubt his presidential temperament, and the status of his health.

Ted Newton, managing Project Goldfish under Myers, had come into the vet liking Christie for his brashness and straight talk. Now, surveying the sum and substance of what the team was finding, Newton told his colleagues, If Christie had been in the nomination fight against us, we would have destroyed him—he wouldn’t be able to run for governor again. When you look below the surface, Newton said, it’s not pretty.